Future Technologies

6G Native Trustworthiness

In this paper, we first propose a 6G multi-lateral trust model in which blockchain for wireless networks is introduced as a trusted infrastructure. We then analyze the physical layer security technologies and the widely researched quantum-key-distribution techniques.

Authors (all from Huawei 6G research team): Fei Liu 1, Rob Sun 2, Donghui Wang 3, Chitra Javali 1, Peng Liu 3

- Singapore Research Centre

- Ottawa Wireless Advanced System Competency Centre

- Wireless Technology Lab

1 Introduction

Trust is a prerequisite for information exchange between parties. Trust establishment is founded not only on mutual identification, but also on the security and privacy preservation capabilities embedded into the signaling and data flow throughout the network. A robust network system can proactively identify risks and threats, and take remedial actions in the event of an attack or natural disaster. When all these functions are directly triggered by events, changes, or user requests without manual configuration and scheduling, the trustworthiness is deemed as native. Native trustworthiness can be achieved through a trustworthy architecture design, covering security, privacy, and resilience.

Compared with 5G, 6G networks will be more distributed and provide some unique user-centric services. Such requirements are bound to pose challenges to the current network-centric security architecture. A more inclusive trust model is required. It is therefore necessary to propose a native trustworthiness architecture that covers the entire lifecycle of communications networks.

In the following sections, we report our explorations of appropriate and effective trustworthiness-related technologies for 6G.

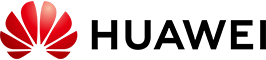

Wireless communication was first introduced in the 1980s. In the subsequent years, it has gone through revolutionary transformation in security architecture. The first generation, 1G, was based on analog transmission that was prone to eavesdropping, interception, and cloning. 2G introduced the technique of digital modulation and was able to provide some basic security features. Figurer 1 illustrates the security architecture evolution from 3G to 5G. 3G introduced two-way authentication and Authentication and Key Agreement (AKA), overcoming the limitations of one-way authentication in 2G.

4G features more connection modes compared with its predecessors. The Diameter protocol used in 4G, however, is vulnerable to attacks, including attacks that track user location and intercept voice transmission to access sensitive information. Other security risks with 4G include downgrade attacks, intercepting Internet traffic and text messages, causing operator equipment malfunctions, and carrying out illegitimate actions.

5G architecture is service-oriented, with many improvements to security introduced. 5G provides more efficient and secure mechanisms such as unified authentication; Subscription Concealed Identifier (SUCI), which hides the subscriber ID during authentication; protocol-level isolation between slices; and secondary authentication serving service providers. The Security Assurance Specifications (SCAS) require that all network functions be tested by accredited evaluators so as to provide a reference for operators.

Figure 1 3GPP security architecture evolution

5G security architecture is almost perfect. However, it is applicable to a centralized network architecture and the trust relationships between network elements in 5G are established at the protocol level, not involving device and network behavior. In the 6G ecosystem, trusted connections are key for all parties concerned, which extend security and privacy to a more inclusive framework — trustworthiness.

To build a 6G trustworthiness architecture that serves distributed networks and is compatible with existing centralized networks, adopting new design concepts and developing new 6G-oriented trustworthiness capabilities is the top priority of 6G research.

ITU-T Recommendation X.509 defines trust in the ICT domain as follows: “Generally, an entity can be said to ‘trust’ a second entity when it (the first entity) makes the assumption that the second entity will behave exactly as the first entity expects”.

The ITU-T has been working on trust standardization with a focus on the ICT domain since 2015, and has released several recommendations and technical reports that describe the architectural and technical views of trust. The study of trustworthiness started with IoT as the first application domain. There were also reports and standards published that laid out the strategies to explore trust in other application domains like cybersecurity and networks. In 2017, trustworthiness was defined by NIST for the first time in the CPS domain as, “demonstrable likelihood that the system performs according to designed behavior under any set of conditions as evidenced by characteristics including, but not limited to safety, security, privacy, reliability and resilience.” Subsequently, in 2018, ITU-T approved the research for a new framework of security that focuses on establishing trust between entities in the 5G ecosystem.

Researchers have explored trust relationships extensively, applying different methodologies, such as game theory and ontology, and analyzing risks in cloud-based modes. On the commercial side, several vendors and operators have been striving to meet consumer demands by continuously upgrading their product design and development, in which the “security by design” concept is emphasized and standardization policies are followed. All in all, it is imperative to define trustworthiness for future 6G communication networks.

2 Fundamentals of 6G Trustworthiness

In the following section, we explain the 6G trustworthiness framework we propose, which encompasses two vital principles, three objectives, and a multi-lateral trust model.

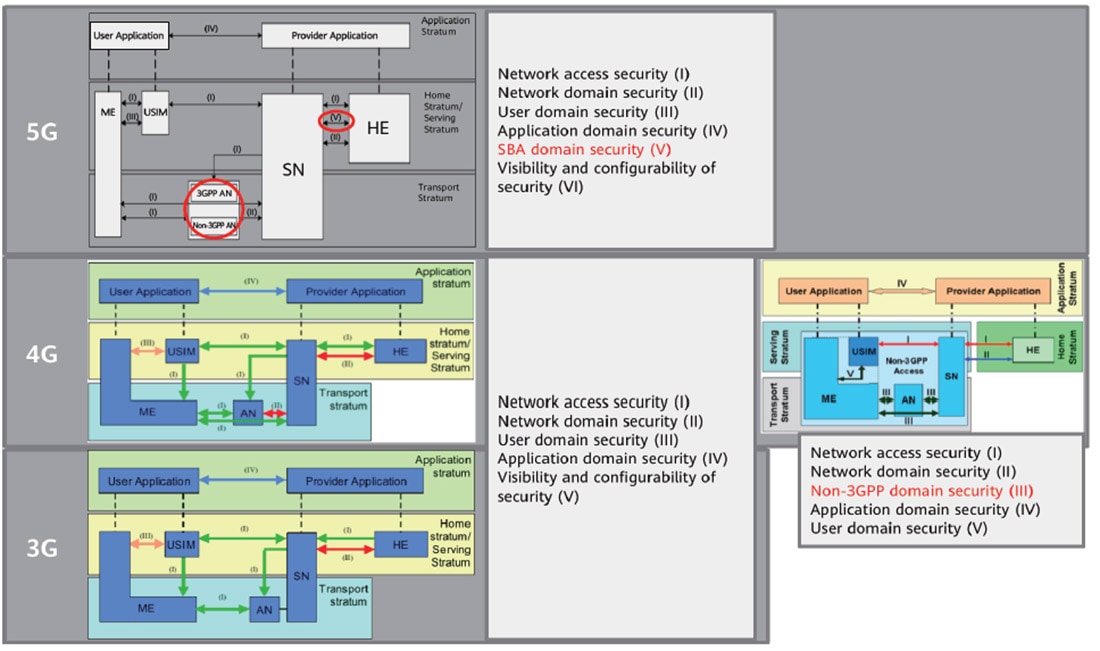

Figure 2 Trustworthiness framework

2.1 Principles

There are two principles to follow in the design of 6G native trustworthiness architecture.

- Principle 1: Trustworthiness of 6G characteristics

Driven by intelligent networks, 6G applications range from sensor networks to critical healthcare and satellite communications. 6G trustworthiness must be able to meet the different requirements of holistic networks and diverse applications based on their technical and business domains, and be quickly adaptable for applications that require centralized authority and edge autonomy.

- Principle 2: Trustworthiness inherent in the 6G lifecycle

Trustworthiness requirements must be considered in tandem with network requirements in the entire 6G lifecycle, from design to development, operations, and maintenance. And trustworthiness analysis, assessment, and evaluation must be continuously performed to achieve satisfactory results.

2.2 Objectives

Security, privacy, and resilience are the three pillars of 6G trustworthiness. Each of the pillars are underpinned by unique underlying attributes, as shown in Figure 2. To achieve trustworthiness in 6G networks, 6G network architecture must meet the following objectives with regard to the three pillars:

- Objective 1: Balanced security

Security is supported by three attributes: confidentiality, integrity and availability (CIA). One of the essential criteria for 6G native trustworthiness is the ability to weigh the three attributes adaptively based on the applications and scenarios and ultimately achieve a balance between network quality/user experience and security capabilities.

- Objective 2: Everlasting privacy preservation

User identity, user behavior, and user-generated data are the three types of data concerning privacy protection on a network. Only authorized parties can interpret information that reveals a user’s identity and behavior. In 6G networks, user identity and user behavior are unique, which is rooted in the unified definition of user identity and the composition of signaling messages. User-generated data is not stored on the telecom network and is protected in the process of data processing and operations using techniques such as encryption and security management.

- Objective 3: Smart resilience

Resilience centers on risk analysis in a network. There are several stages of risk management. The first stage is to identify the risk factors. The second is to take suitable measures to avoid these risks by leveraging big data analytics. If the risks cannot be avoided, they can be transferred to other entities so that the network can be recovered successfully. The after-effects must be controllable to the minimal level. If the preceding measures cannot be taken, the final stage is to accept the risks that cause only non-fatal damage to the network.

2.3 Multilateral Trust Model

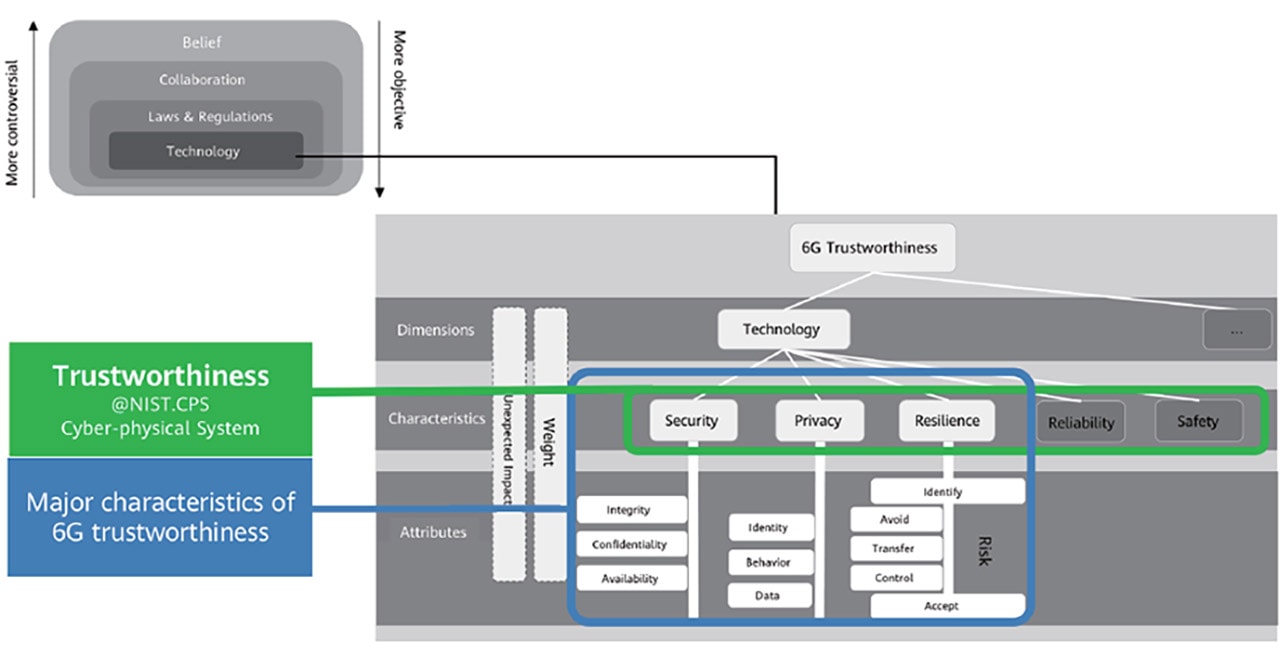

As shown in Figure 3, we have introduced a multilateral trust model in 6G to meet the needs of various trust scenarios.

Figure 3 Multilateral trust model

A multilateral trust model includes three modes: bridge, endorsement, and consensus. In bridge mode, an accreditation authority authenticates and authorizes entities A and B respectively, transfers trust between the two entities, and eventually establishes trust between them. The endorsement mode involves relying on third parties to evaluate an entity’s trustworthiness. In this mode, a third party evaluates an entity’s trustworthiness and submits the evaluation result to the other entity. The consensus mode is the most significant of the three as it adopts a decentralized architecture where transactions are distributed among entities. The entities involved in the consensus mode can be elements on a network, parties in a supply chain, or organizations in an industrial ecosystem. In this mode, transactions are attestable and responsibilities are shared among multiple parties, providing high efficiency and scalability and enabling it to meet the agile and customized access requirements of 6G.

The three modes of this model should all be duly considered in the design of security architectures and mechanisms. The enabling technologies for the three modes should all be researched and developed, including the identity management and authorization technologies applicable to the bridge mode, the third-party security evaluation technologies suitable for the endorsement mode, and the blockchain technology ideal for implementing the consensus mode.

3 Enabling Technologies for 6G Trustworthiness

3.1 6G Blockchain

To establish a trust consortium based on which multiple parties can have mutual trust for resource-sharing and transactions can be performed autonomously, a customized blockchain for wireless networks is needed. 6G blockchain will serve as the basis for traceability mechanisms that ensure trust.

The following sections describe the convergence of blockchain and communications networks, blockchain technology under the privacy governance framework, and blockchain technology customized for wireless networks.

3.1.1 Convergence of Blockchain and Communications

6G blockchains can be classified into three types: independent blockchain, coupled blockchain, and native blockchain, depending on the degree of coupling between blockchain and the communications network.

- Independent blockchain

Independent blockchains are independent of the communications service and protocol processes, providing data storage and traceability for network O&M and management. Typical applications include roaming billing and settlement. These interactions, though not included in the signaling flows defined by 3GPP, are significant for establishing trustworthy relationships between operators and enhancing efficiency by utilizing smart contracts.

- Coupled blockchain

Coupled blockchains are those that interact with the communications network in the protocol process. The interactions include offline chaining and online checking. Take blockchain-based authentication as an example: The information owner or an authorized operator stores some information, such as a credential or hash values, into a blockchain in advance. When a communication request is initiated, the receiver authenticates the requester by looking up its credential in the blockchain, during which the requester waits for a response. If the authentication is successful, the receiver accepts the connection request and continues with the subsequent process.

- Native blockchain

A native blockchain refers to a blockchain whose algorithms, communication protocols, and enabling functions are all inherent in communications networks. Writing to the blockchain and searching in it both occur online and in real time as part of the communication process. However, the real-time application of blockchain technology in communications networks faces many new challenges. One of the goals of 6G is to create a real-time, large-scale blockchain system that serves as the foundation for network operational trustworthiness, so that every real-time data session and every real-time signaling transaction will be immutably recorded, for example, on a privilege-based super ledger. Thus, there is the need to design a 6G customized blockchain architecture featuring low latency and high throughput, which satisfies the potential requirements of wireless communications and networks and also meets privacy protection objectives.

3.1.2 Blockchain Compliant with Privacy Protection Framework

In recent years, a number of personal data privacy and security laws have been implemented around the globe, for example, Data Security Law of the People's Republic of China (PRC), Act on the Protection of Personal Information (Act No. 57 of 2003), CLOUD Act, and California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) being one of the strictest.

According to Article 5 of GDPR, all processing of personal data must follow the principles of:

- Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency

- Purpose limitation

- Data minimization

- Accuracy

- Storage limitation

- Integrity and confidentiality

- Accountability

Cryptography, if applied appropriately, can help in complying with these principles. Given that, we are working on developing 6G oriented cryptographic solutions for customizing a 6G blockchain.

The following describes the zero-knowledge proof system, one of the preliminary ideas we proposed about privacy preservation on a 6G blockchain, which marks the start of our research.

In the Nakamoto model all transactions in a blockchain are in plain text. Hence, a native privacy algorithm needs to be implemented to ensure that the data storage in a 6G blockchain is compliant with GDPR and other privacy regulations. The state-of-the-art technology zk-SNARK (zero-knowledge succinct non-interactive argument of knowledge) is computationally complex, because it requires several iterations to find the arithmetic roots of a polynomial equation and thus attain a soundness error within a threshold. Complexity is also involved in the trusted setup that involves computation of many cryptographic algorithms and time-consuming operations. The variants zkBoo and zkBOO++ have eliminated the requirement of trusted setup and employ garbled circuit, which is different from the arithmetic circuit used by zk-SNARK. However, they still use the monolithic statement for contract verification and auditing is a drawback, so they cannot be used practically for large systems.

We propose zk-Fabric, a native privacy framework based on the zero-knowledge proof system. It has the following features:

- The input parameter size is linear to the input.

- The solution is realized by Boolean gates circuit.

- The semantic statements from the prover are transformed to polylithic syntax.

- A non-interactive oblivious transfer (OT) based multi-party joint verification system is adopted.

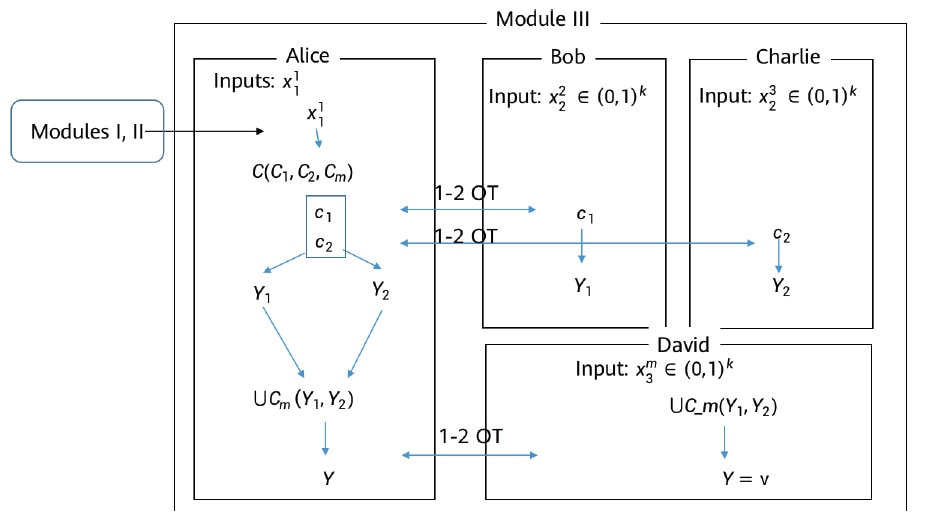

Figure 4 shows the zk-Fabric framework consisting of three modules. The objective is to verify the statements of Alice anonymously without revealing secrets. Alice transforms her input statements into a Turing complete Boolean circuit with the decomposition algorithm in Module 1 (polylithic syntax decomposition) and partitioned garbled circuits for multiple verifiers in Module 2 (garbled circuit generation). The information is published on a publicly accessible blockchain. In Module 3 (multi-party non-interactive OT), the multiple verifiers verify the statements through the online public system.

Figure 4 zk-Fabric framework

The zk-Fabric allows a cluster of verifiers to anonymously and jointly compute a succinct digest of garbled circuits C online, which is prepared by a prover who also partitions the garbled circuit and randomly dispatches segments of them to a publicly accessible repository, i.e. a blockchain or web portal. The goal is to build a more comprehensive public verification system that can validate more complex statements than other technologies capable only of performing a monolithic verification where verification can only conduct one hashed value in an arithmetic circuit at a time. The zk-Fabric framework also achieves full privacy preservation computation (encrypted computation) based on OT and garbled circuit.

For security evaluation, we demonstrate that zk-Fabric can maintain privacy against the semi-honest threat model (Note: zk-Fabric may not be sufficient in protection against the "Malicious" model). We can formalize this using a generalized Fiat-Shamir's secret sharing scheme, which defines a secure n-party protocol that packs l secret into a single polynomial. One can run a joint computation for all inputs by just sending a constant number of field elements to the prover. As a result of packing l secret into a single polynomial, we can reduce the security bound t of zk-Fabric with multiple verifiers as t = -n -1 to t’ = t - I + 1 . In zk-Fabric, OT is a very useful building block towards achieving protection against semi-honest participants.

For computational efficiency, we demonstrate that zk-Fabric can achieve efficiency with two key refinements. First, we employ the Karnaugh Map technique to reduce the number of logical gates with a simplified expression. Second, we build garbled circuits with partitions by tightly integrating the verification procedure with a multi-party OT scheme. This reduces computational costs on the verifiers' side compared with native approaches.

Note that our security definition and efficiency requirements immediately imply that the hash algorithm used to compute the succinct digest must be collision resistant.

Inspired by the security notions of OT-Combiners, we have started by constructing an overall zk-Fabric system that builds on the partitioned OT scheme. Figure 5 shows an example of two polylithic inputs to be “blindly” verified by three offline verifiers with the construction of partitioned garbled circuits.

Figure 5 zk-Fabric system

3.1.3 Blockchain Customized for Wireless

6G networks feature faster data transfer rates, lower latency, and more reliable communications than their predecessors. The following provides some key data relating to 6G:

- Peak rate: 100 Gbit/s to 1 Tbit/s

- Positioning accuracy: 10 cm indoors and 1 m outdoors.

- Communication delay: 0.1 ms

- Battery life of devices: up to 20 years

- Device density: ~100 devices per cubic meter

- Downtime rate of devices: one millionth

- Traffic on communication channel: about 10,000 times as much as that of today's networks

However, bitcoin currently has a transaction throughput of seven transactions per second (TPS), Ethereum has a transaction throughput of 15–20 TPS, and Hyperledger Fabric has a transaction throughput at an order of magnitude of up to 103. The low throughput of blockchain transactions sharply contrasts with the high performance of 6G. In most service scenarios, particularly high-frequency trading scenarios, current blockchain cannot meet actual application requirements. Therefore, we need to continue researching the consensus algorithm in blockchain to improve consensus efficiency and enhance scaling techniques. Meanwhile, we need to boost throughput from the aspect of system architecture.

Based on the six-layer blockchain architecture model, popular capacity expansion technologies can be classified into three schemes depending on the layers.

- Layer-0 scalability optimizes the data transmission protocols at the network and transport layers of the OSI model, without changing the upper-layer architecture of the blockchain. It is a performance improvement solution that retains blockchain ecosystem rules. Layer 0 scalability involves relay network optimization and OSI model optimization.

- Layer-1 scalability (on-chain scalability) optimizes the structure, model, and algorithms of the blockchain across the data layer, network layer, consensus layer, and incentive layer to improve the blockchain performance.

- Layer 2 scalability (off-chain scalability) executes contracts and complex computing off the chain to reduce the load on the blockchain and improve its performance. Off-chain scalability does not change the blockchain protocol. The current technologies for off-chain scalability include payment channel, sidechain, off-chain, and cross-chain technologies, among others.

The “scalability trilemma” states that any blockchain technology can never feature all three organic properties of blockchain — scalability, decentralization, and security. When scalability is enhanced, decentralization and security will be compromised. Therefore, research on 6G blockchain is not just about improving throughput. It should also cover selecting appropriate technology paths based on the 6G characteristics to strike a balance among the three properties of blockchain and to ensure its adaptability to 6G scenarios.

3.2 Quantum Key Distribution

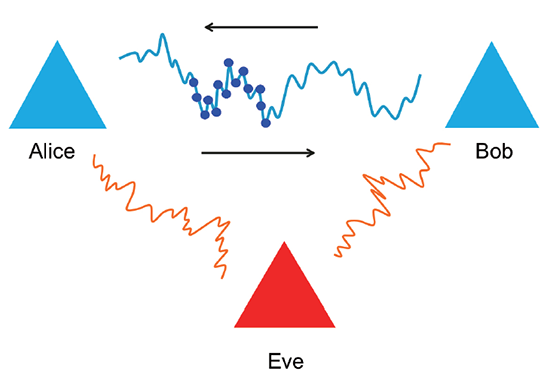

The first quantum key distribution (QKD) protocol was proposed by C.H.Bennett and G. Brassard in 1984 and is known as BB84 after its inventors and year of publication. In this protocol, the sender (Alice) and the receiver (Bob) wish to agree on a secret key. Alice sends Bob each bit of the secret key in a randomly selected set of conjugate basis through transposition quantum gate transformation. An eavesdropper (Eve), unaware of the basis used, cannot decode the quantum bit (qubit) by measuring in the middle, as once a qubit in transposition is being measured by the eavesdropper, it collapses into a state that ultimately introduces errors in Bob’s measurements. This is known as the non-locality theorem.

BB84 and its variants are designed for point-to-point (Alice to Bob) setup, which has its limitations. For example, it remains a challenge to deliver entangled qubits to more than two parties. In this paper, we discuss a multi-user (MU) QKD protocol that utilizes two entangled qubits to deliver a secret key to multiple parties with n = 3. In our design, we utilize a centralized trust model in which a key operator (O) can manage the subgroups of nodes, and the subgroups rely on the operator (O) to distribute the key securely through the QKD protocol. Through the quantum correlation routine at the operator over the authenticated classic channel, all three parties obtain the shared key.

As an extension, the MU QKD protocol can be applied to more than three parties by keeping the operator as the trust anchor point and iteratively reusing the three-party MU QKD protocol. Thus the shared key can be obtained by n = 2ℓ + 1 nodes.

The MU QKD protocol can be put into extensive practical use given its broadcast nature, with security ensured by the underlying quantum physics. One of the applications is mobile phone key distribution, where a key operator is able to multicast the pre-shared key for authentication to multiple end nodes. Another application is for quantum repeaters. A prominent challenge in transmitting qubits on quantum Internet is that qubits cannot be copied, which naturally rules out signal amplification or repetition for overcoming transmission losses and bridging great distances. To enable long-distance quantum communication and implement complex quantum applications, most current literature models the quantum repeater with "Store and Forward" quantum mechanics such as Quantum Memory. "Store and Forward" qubits manipulation breaks down the point-to-point basis of QKD, making it hard to obtain end–to-end provable security.

3.3 Physical Layer Security (PLS)

Higher frequency bands, such as millimeter waves and terahertz waves; higher bandwidth; and larger antenna arrays in 6G networks open up new horizons for the design and development of physical layer security. In this article, physical layer security refers specifically to the use of physical layer technologies for security.

The following key characteristics of 6G wireless signals can be leveraged to provide secure communication between legitimate parties:

- Multi-path fading: As wireless signals are transmitted, they undergo large- or small-scale propagation fading as the result of obstruction by objects, such as buildings and hills, during transmission. Moreover, reflections and scatterings from various objects cause multi-path fading and the components of the signal vary with distance.

- Time-varying: The wireless signals exhibit time-varying property as both the transmitter and receiver are on-the-go and the radio waves experience scatterings, reflections, and refractions due to the presence of many stationary and moving objects around.

- Reciprocity: Wireless channels are reciprocal in space, implying that channel responses can be estimated in either direction if measured within the channel coherence time.

- Decorrelation: The channel responses exhibit rapid temporal and spatial decorrelation.

3.3.1 Physical Layer Technology Contributing to Secret Key Generation

The decorrelation and reciprocity of wireless signals can be leveraged to extract secret keys between two legitimate entities. Researchers have leveraged physical-layer based features for secure device pairing and secret key generation. Secret key generation consists of two steps: (i) channel sampling and (ii) key extraction. In the first step, the two legitimate entities exchange a series of probes to measure the channel between them. The channel measurements can either be in the frequency or time domain. In the second step, the channel measurements are converted to a sequence of secret bits through quantization. This extracted key can be combined with higher layer security algorithms for encryption. Given the presence of the passive adversary Eve who eavesdrops all signals transmitted between the two parties, the channel estimate will not correlate with those of either Alice or Bob as the signals undergo multi-path fading. It is a challenging task for Eve to retrieve the same secret keys as the legitimate parties do. As shown in Figure 6, the legitimate devices observe similar characteristics whereas the eavesdropper gets different channel estimates.

Figure 6 Channel characteristics between legitimate and non-legitimate devices

The following describes the basic physical layer metrics that are essential to measure security performance:

- Entropy is the amount of randomness in the information content and is defined by:

H(M) = - ∑ p(m)log p (m)

where p (m) is the probability that takes on the value of message M.

- Mutual information is a quantity indicating how secure a communication channel is. If the mutual information between message M and the encrypted message X intercepted by Eve is zero, the communication channel is considered secure. It can be expressed as:

I (M; X) = 0

Or, it can be expressed in terms of entropy as:

I (M;X) = H(M) – H(M|X)

where H (M|X ) is the conditional entropy defined as the remaining uncertainty in message M after observing the encrypted message X.

- Secrecy rate is the rate at which a message is transmitted

to the legitimate receiver, while being intercepted by Eve. It is expressed as:

\( C_{s}=C_{B}-C_{E} \)

where CB and CE are the secrecy rates of Bob and Eve, respectively. The secrecy rate can be increased using signal design and optimization techniques.

- Secrecy outage probability is the probability at which a specified value of secrecy capacity Cs cannot be attained by a system. Here, limited channel information of Bob and Eve is available to Alice.

Bit error rate (BER) is the number of bit errors received divided by the total number of bits transmitted. The BER for legitimate entities must be lower than that for adversaries.

3.3.2 Physical Layer Technology Contributing to Authentication Protocol

Research has also been carried out on the physical layer technologies used for security authentication. Researchers proposed using indoor-based Wi-Fi channel characteristics for generating the proof of location of mobile users. Proof of location is evidence that attests a user’s presence at a particular time and location. This proof is provided by a trusted entity for mobile users. With this proof, the mobile users can be verified for authenticity by the service providers. The research demonstrates that proof of location is kept secure, has not been tampered with or modified, or transferred to other users.

4 Privacy Preservation

‘Personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or by one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person. In telecom networks, personal data can be categorized into three types: user IDs, user-generated data, and user behavior.

- User IDs

A telecom network assigns users with personal IDs such as lifetime network IDs, service IDs, and fine-granularity temporary IDs. On a telecom network, personal IDs are fully protected. In 5G, initial IDs used for user authentication on the network are protected by end-to-end encryption.

- User-generated data

User-generated data, such as the contents of a phone call and an application on the

Internet, are neither stored on the network nor analyzed by operators. Such data is encrypted during transmission and cannot be understood by interceptors.

- User behavior

The behavior of UEs accessing, leaving, or performing a handover can be observed on the control plane. To hide user information, the network provides an encryption scheme for signals. If the signal encryption is not implemented on the network, user habits, such as the frequency of phone calls and the movement between locations, can be estimated by tracing the user and observing signaling changes.

In the 6G era, it will be a challenging task to preserve privacy and protect personal information. With AI-enabled decision-making for applications, consumers will be able to enjoy services tailored to their preferences, but they may not be aware of the unprecedented amount of personal data that has to be collected for such personalized services. For instance, autonomous driving and smart-home applications will collect sensitive information such as the user’s location as a user is driving. Using smart appliances will reveal that an individual is at home. Cloud-based storage will open up doors for privacy breaches. A report lists several data breaches that took place in the 21st century, where a number of records and accounts related to individuals were exposed.

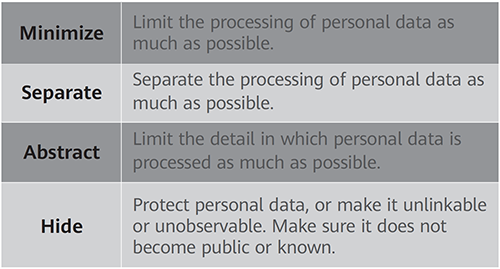

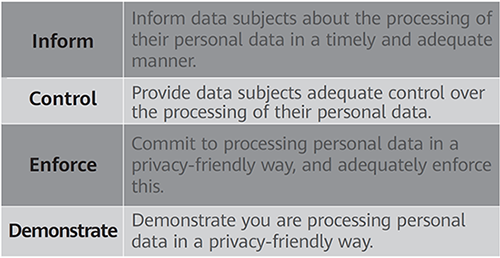

To prevent privacy breaches, privacy preservation must be considered in the design phase of the 6G lifecycle and managed in all stages that involve data usage. ENISA laid out eight privacy design strategies, as explained by Jaap-Henk Hoepman in Privacy Design Strategies. The strategies are divided over two categories: data-oriented strategies and process-oriented strategies. The data-oriented strategies (as shown in Table 1) focus on preserving the privacy of the data themselves and process-oriented strategies (as shown in Table 2), focusing on the methodologies/approaches for data processing.

Table 1 Data-oriented strategies

Table 2 Process-oriented strategies

Several privacy enhancing technologies have been researched in depth for more than a decade. This research focused on minimizing personal data to avoid any unnecessary process-oriented tasks. Following are some of the privacy enhancing technologies:

- Homomorphic encryption (HE) allows computations to be performed on encrypted data. The results are encrypted and no information about the data is revealed. Users can decrypt the data and analyze the results. HE can be classified into partial HE and full HE. The pioneering work on HE dates back to 2009 when Gentry proposed the first full HE scheme, and several improved schemes have been introduced over the following years. Even so, the implementation of HE was limited as it required a thorough understanding of the HE scheme and the complex underlying mathematics. To address this issue, Microsoft introduced the open source project SEAL to make HE schemes available for everyone. SEAL provides a convenient API interface and many illustration examples to show the correct and secure way of using the interface, along with related study materials. Traditionally, in applications involving cloud storage and data processing, end users need to trust the service provider responsible for storing and managing data, and the service provider must ensure that user data is not exposed to any third parties without the user’s consent. SEAL manages this concept systematically by replacing trust with well-known cryptographic solutions. This not only enables encrypted data to be processed, but also guarantees the protection of user data. Below we explain the important factors to consider when designing solutions with HE:

- Performance overheads are very large, since HE increases the original data size by several times. Thus, it is not recommended for all applications.

- In HE solutions, a single secret key is held by a data owner. Thus, co-computing between multiple data owners requires a multi-key fully homomorphic scheme.

- The security property of homomorphic encryption determines that it can only provide passive security, but cannot guarantee the security of applications using it in the active attack environment.

- Zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) is a cryptographic technique that verifies information without having to reveal the information itself. Researchers at MIT developed this concept. A ZKP protocol must satisfy the following properties:

- Completeness: If the prover submits legitimate information, then the protocol must allow the verifier to verify that the information submitted by the prover is true.

- Soundness: If the prover submits false information, then the protocol must allow the verifier to reject the claim by the prover.

- Zero-knowledge: The method must only allow the verifier to determine the authenticity or falsity of the information submitted by the prover without having to reveal anything.

ZKP can be categorized into interactive ZKP and non-interactive ZKP. As the name suggests, in interactive ZKP there are several interactions between verifier and prover, and the verifier challenges the prover several times until the verifier is convinced. However, in non-interactive ZKP there is no interaction between the two parties. zk-SNARK (zero-knowledge succinct non-interactive argument of knowledge) and zk-STARK (zero-knowledge scalable transparent argument of knowledge) are non-interactive ZKP protocols. zk-SNARK was first used in the Zerocash blockchain protocol which enables a participant to prove its possession of particular information without revealing the information itself. zk-STARK was released in 2018 offering transparency i.e., no requirement of trusted setup and poly-logarithmic verification time.

- Secure multi-party computation (SMPC): As an extension of HE, SMPC allows multiple parties to work on the encrypted data, with no party being able to view the other parties’ information. This ensures that data is kept private in SMPC. The natural advantage of SMPC has encouraged several research projects on machine learning to ensure privacy. Facebook AI has developed CrypTen, a privacy preserving framework based on SMPC. It is a software built on PyTorch, and researchers familiar with machine learning can call the API to build applications for preserving privacy.

- Differential Privacy (DP) protects the privacy of individuals by injecting statistical noise into the dataset using a cryptographic algorithm. The noise layer helps distinguish different groups in a particular dataset. Although the proposed method has very little impact on data accuracy, it ensures plausible deniability and hence preserves the privacy of individuals. In DP systems, a user needs to submit “query” to obtain the data of interest. The system then performs an operation known as “privacy mechanism” to add some noise to the data requested. This function returns an “approximation of the data”, thereby hiding the original raw data. The output “report” of a query consists of the privacy-protected result along with the actual data calculated and a description about the data calculation. The following are two important metrics in DP:

- Epsilon: It is a non-negative value that measures the amount of noise or the privacy of output report. It is inversely proportional to noise/privacy; that is, a lower Epsilon means more noise/private data. If the Epsilon value is larger than 1, it indicates that the risk of exposing actual data increases. Hence, the ML/AI models must aim to limit the value within the range of 0–1.

- Delta: It measures the probability of the report being non-private. It is directly proportional to Epsilon.

DP systems mainly aim for data privacy. However, one must be aware of the underlying tradeoff between data usability and data reliability. If the noise and privacy level increases, the Epsilon value reduces, and the accuracy and reliability of data decreases.

The popular open source project SmartNoise aims to help the implementation of DP in ML solutions. It has two main components:

- Core Library, where many privacy mechanisms are stored

- SDK Library, where tools and services required for data analysis are stored

5 AI Security and Trust

In 6G, services and applications will be highly intelligent and autonomous. The E2E architecture of 6G will be based on blockchain and AI. This will involve working on a tremendous amount of data, and decision-making of the network will be entirely based on data analytics. Therefore, AI systems need to be secure throughout the machine learning lifecycle, which mainly consists of data acquisition, data curation, model design, software build, training, testing, and deployment and updating. In each stage of the lifecycle, confidentiality, integrity, and availability must be ensured to keep the model secure. If security is not prioritized in the early stages of the lifecycle, then malicious actors can tamper with models for many important applications like healthcare and autonomous driving, leading to severe consequences.

Different types of attacks are as follows:

- Poisoning: An AI model is compromised by attackers and does not behave in the way it is designed to perform a specific task, but rather behaves in a way the attackers want it to. A malicious actor can launch such an attack by (a) poisoning the data set, i.e. injecting incorrect data into the training data set or incorrectly labelling the data, (b) poisoning the algorithm, or (c) poisoning the model.

- Evasion attack: Data inputted during deployment or testing is tampered so that the learned model deviates from the correct results. An example of an evasion attack is the modification of traffic signal, where a minor modification will lead to an autonomous car misinterpreting the traffic signal and making an incorrect decision.

- Backdoor attack: Such an attack is triggered only when a specific pattern is input to a model. The model behaves normally when provided with inputs not in the triggering pattern. Hence, it is a challenging task to validate if a model is subject to or compromised by a backdoor attack. This kind of attack can happen in both training and testing. If an attacker injects input in the attack-triggering pattern to the model during training, undesired results will be outputted by the model after it is deployed.

- Model extraction: An attacker analyzes the input, output, and other related information of the target model and performs reverse engineering to construct a model that is the same as the target model.

There are different defense mechanisms for the afore-mentioned attacks. Adversarial training is the approach of feeding adversarial inputs to the training dataset and optimizing the model iteratively until it behaves correctly. This method can improve the robustness of models against predicted attacks. Adversarial training can be used to defend against evasion attacks. Another defense mechanism is defensive distillation, which is based on the concept of transfer learning of knowledge from one model to another. A model is trained to perform the probabilities of another model that is trained to provide accurate outputs.

However, these defense mechanisms may not be able to ensure security against all attacks. Some other methods should also be considered, such as noise injection, enhancing the data quality during the training phase, and inserting an additional layer that detects the attacks on the model. Synergizing multiple defense approaches can help make AI more secure and robust.

6 Measurement, Verification and Attestation

As described previously, trustworthiness embodies three foundation pillars: security, privacy, and resilience. Assessing the trustworthiness of a system inherently involves evaluating the three foundation pillars continuously and iteratively throughout the 6G lifecycle. In this section we explain the methodologies that can be adopted in this regard.

6.1 Security Analysis

Security analysis of network protocols can be conducted in two approaches: (i) logic and symbol computation and (ii) computational complexity theory. The first approach uses cryptographic primitives and is the foundation of many automated tools, whereas the second approach involves reasoning and computational complexity and scores the strengths and vulnerabilities of the protocols. Some of the tools used for security analysis of protocols are: Tamarin prover, ProVerif, AVISPA, and Scyther. The 6G E2E architecture will involve authentication and key agreement protocols between various entities. It is therefore essential to perform security analysis of the protocols to identify vulnerabilities and security loopholes and prevent devastating outcomes.

6.2 Privacy Protection Framework and Privacy Verification

Network privacy must be considered as early as in the design phase. GDPR requires that organizations comply with all privacy requirements. Data controllers must frequently review and audit the process of data-oriented tasks and ensure that these tasks adhere to data protection policies. GDPR also offers the privacy certification service, which indicates to customers that certified organizations will adhere to the standards of data privacy and protection. This certificate is already used by some products and websites. Also, GDPR has proposed an initiative — PDP4E that provides software tools and methodologies for organizations to validate whether their applications and products comply with the GDPR policies. The tools mainly focus on four aspects:

- Privacy risk management

- Gathering privacy-related requirements

- Privacy and data protection by design framework

- Assurance framework

6.3 Trustworthiness Measurement and Security Evaluation

To achieve trustworthiness, it is also necessary to continuously measure network resilience. Risks have to be identified and analyzed and timely action must be taken to prevent serious consequences. Similar to the quantitative measurement of quality of service (QoS) and quality of experience (QoE), ITU-T has mentioned that a quantitative method can be employed to measure trustworthiness. This trustworthiness, however, is application-specific and dependent on the use scenarios. In addition, security risks can be evaluated either quantitatively or qualitatively. The quantitative measurement, as the name signifies, assigns a numeric value as the risk level, whereas the qualitative approach assigns a rating based on the possible consequences. Risk analysis can be performed to re-consider/re-evaluate security solutions, thereby eliminating threats and mitigating risks.

7 Conclusion

The 6G network needs to aim for seamless intelligent connectivity of all devices that have network capabilities. Compared to all the previous generation technologies, 6G will raise the level of user experience. As 6G will extend the massive machine communication, ultra-low reliable latency, and enhanced mobile broadband – the three pillars of 5G – to sensing and AI, ensuring a trusted network becomes a challenging task. In this paper, we have first presented the fundamentals of 6G trustworthiness architecture i.e., the principles and objectives and the multi- lateral trust model design for 6G. The enabling technologies for 6G viz., blockchain, quantum key distribution, and physical layer security, have also been discussed.

6G networks will collect and process significant amounts of data to provide network services by applying artificial intelligence and machine learning. Hence, preserving the privacy of consumers will be of paramount importance in future networks. Privacy by design principles that explain the design strategies in the 6G lifecycle have been discussed in the paper along with the potential technologies that preserve privacy. Furthermore, AI as one of the main enablers in 6G architecture, can act as both a defense and an attack, as covered in this present paper. Finally, the approaches to assess the trustworthiness of a system is presented in the paper. Extensive research is still to be undertaken to meet the challenges of security and privacy issues in tandem with the 6G enabling technologies. We hope that this paper will act as a catalyst and help researchers and scientists to pursue further advanced research that will help in standardizing 6G technologies.

- Tags:

- 6G